Authors: Stijn van den Oever, Adam Calo, Heidi Vinge, Beste Sabir Onat

The JUST GROW team based in Norway and the Netherlands is investigating how urban agriculture is mediated by land access and labour equity. During the summer period the pace of our research has slightly slowed down, but now that everyone is back (and especially since Beste has joined the team!) we are ramping up our efforts to investigate this dimension. The summer gave us time to reflect on the exciting interviews we’ve done so far, and we would like to share some of these insights here.

In our interviews we have found that novel and unconventional urban farms are more responsive to our invitations than the conventional farms. We realize that an important next step would be to actively include these conventional farms, but on the other hand it allowed us to visit some very interesting forms of urban agriculture. Among these are a vertical farm, a floating farm and a city farm (with lands scattered throughout the city). The people running these farms have several traits in common. First, they are extremely entrepreneurial and have found an innovative form of farming in which they see a future. The vertical farm has developed a fully automated method of production that takes place inside a shipping container. By stacking containers on one another they bypass land-access issues while simultaneously reducing the dependency on field workers.

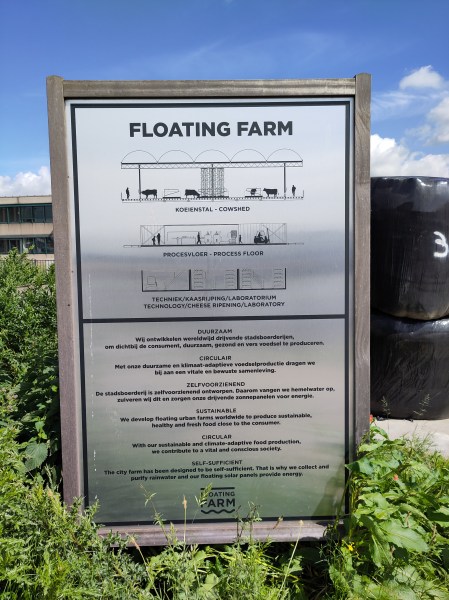

Second, the sites we have interviewed reveal a strong anticipation and preparation for future problems. The farmers of the floating farm foresee sea level rise as a major threat to Dutch agriculture and thus their model wagers: what type of farm is better equipped against this than one that floats? Besides, with increasing urbanization, a floating farm can still produce food close to a city by creating new land on seas, rivers and lakes that almost all cities have.

Finally, early interviews highlight the importance of a healthy connection between cities and food production. Many interviewees mentioned that some children from the city can’t fully explain how milk is produced, and they see it as part of their job to educate the urban peoples by reestablishing a connection between the city and farming. The farmer of the city farm does this by farming within the new residential areas of the city and actively organizing events to get people to visit farms and educate them on farming practices.

A peak into one of the vertical farm containers [left]. Stijn’s protection outfit for entering the vertical farm [right].

Perhaps the most intriguing common trait emerging from learning from these farms and farmers is that mobility appears as a crucial dimension to the problem of farmland access and labour equity. The vertical farm can pick up their containers and move, the floating farm can be shipped somewhere else, and the city farm leases unused plots of land from governmental institutions and they are flexible in moving their practices between these plots. It isn’t a coincidence that they are all mobile in one way or the other.

Design of the floating farm

So far, the importance of mobility in urban farming to keep access to land is a hypothesis we would very much like to further explore. We as a team are wondering whether more conventional farms experience the same long-term land access uncertainty and whether the importance of mobility is restricted to the Netherlands only or if we will find the same for Norway (and other countries later on). What is ensuring mobility is a broad strategy for ensuring urban agricultural production can address land access barriers? Mobility is also a central theme within broad debates about labor justice and the structure of the agricultural workforce. Perhaps mobility is a key lens to analyze the governance of urban agriculture across a variety of the JUST GROW domains. We are excited to start our next round of interviews and hope to share many more insights with you!

All farmers – also those not mentioned in this blog – told us that they need more security in future access to the lands from the government. Some are dependent on the goodwill of government officials and as soon as they change their mind or are replaced, they need to move. Others are not seen as real farms and thus fall between standard categories when applying for leases and licenses. A third barrier is that Dutch governmental institutions that own land (such as provinces, municipalities and Staatsbosbeheer) prefer short-term contracts to keep control over their lands to be able to respond to future demands. This may be viable when governments could extend the lease for a specific farmer without consequences. However, since a Dutch high court ruling in 2021, they have to offer everybody equal opportunity for a new lease every time the last one expires. In combination with the short-term leases the government prefers, this is not viable for farmers that are dependent on these kinds of arrangements because it takes some years to improve the soil quality of land to make it suitable for cultivation. Farmers thus need longer term security for their farming practices than the government can offer.

Read more about the work of our WP2 research hub and the JUST GROW consortium here!